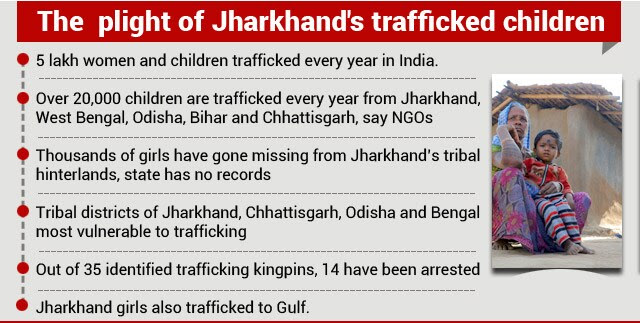

Selling girls a business in Jharkhand, everybody has a share in the 'trade'

- B Vijay Murty/Saurav Roy, Hindustan Times, Simdega/ Khunti/Lohardagga |

- Updated: Mar 02, 2015 21:51 IST

A 2013 report by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime identified Jharkhand as one of the states most vulnerable for trafficking of women and children. Here, a woman sits outside her hut at Garja village in Simdega district which is notorious for child trafficking cases.(Parwaz Khan/HT Photo)

As she plays with her five younger siblings and other children outside her thatched hut in Garja Kendatoli, a tribal hamlet in Jharkhand’s Simdega district, Reeta Kumari (name changed) is like any other 13-year-old. But a dark cloud casts its shadow on her cheerful face whenever anyone mentions Delhi.

“I will never go to Delhi,” she whispers when she hears the visiting HT Team talk of the national capital.

As with thousands of children trafficked from Jharkhand every year, Delhi has been very cruel to Reeta. While visiting a market on Republic Day last year, she was lured by two men and a woman to Delhi with a promise of clothes and lots of money.

Once in Delhi, the girl was sold to an agent who got her employment as a maid in a home where she was subjected to sexual and physical assaults. Reeta fled and spent two months at a women’s home before her father brought her back home.

Reeta was one of the lucky ones. Thousands of girls trafficked every year by interstate gangs to metros and states, including Delhi, Bengaluru, Mumbai, Chennai, Haryana, Punjab and Goa, simply disappear without a trace.

Most of girls serve as bonded labour who are not allowed to interact with anyone except their employers. The less fortunate ones are made to work as sex slaves or become surrogate mothers and organ donors.

Revelations by some rescued girls have blown the lid off the flourishing human trafficking racket in Jharkhand’s tribal hinterlands, a hotbed of modern day slavery where family members, neighbours, local politicians and even NGOs are involved in well-organised rings.

Inter-state networks

“I will never go to Delhi,” she whispers when she hears the visiting HT Team talk of the national capital.

As with thousands of children trafficked from Jharkhand every year, Delhi has been very cruel to Reeta. While visiting a market on Republic Day last year, she was lured by two men and a woman to Delhi with a promise of clothes and lots of money.

Once in Delhi, the girl was sold to an agent who got her employment as a maid in a home where she was subjected to sexual and physical assaults. Reeta fled and spent two months at a women’s home before her father brought her back home.

Reeta was one of the lucky ones. Thousands of girls trafficked every year by interstate gangs to metros and states, including Delhi, Bengaluru, Mumbai, Chennai, Haryana, Punjab and Goa, simply disappear without a trace.

Most of girls serve as bonded labour who are not allowed to interact with anyone except their employers. The less fortunate ones are made to work as sex slaves or become surrogate mothers and organ donors.

Revelations by some rescued girls have blown the lid off the flourishing human trafficking racket in Jharkhand’s tribal hinterlands, a hotbed of modern day slavery where family members, neighbours, local politicians and even NGOs are involved in well-organised rings.

Inter-state networks

A 2013 report by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime identified Jharkhand as one of the states most vulnerable for trafficking of women and children. Much of the trafficking is done by placement agencies that are actually organised crime syndicates, the report said.

Another report by the Action against Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation of Children (ASTEC) in 2010 said about 42,000 girls had been trafficked from Jharkhand to metropolitan cities.

The problem, civil society groups say, has become worse as trafficking rings have forged inter-state links to get around enhanced vigil by state governments. One ploy used by traffickers is to take girls from Jharkhand to far-off places like Assam, where they are less likely to attract the attention of police, before sending them to metros like Delhi.

Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi’s Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA) has identified Rangia railway station in Assam as a transit point for trafficked children from eastern states. Around 58 girls, 18 of them from Lohardaga, were rescued from Doboka in Assam in September last year.

Girls from Gumla, Lohardaga, Khunti and Simdega are also taken to Chattisgarh or Orissa and handed over to agents who send them to other destinations.

The BBA also found that agents in Punjab, Haryana and the National Capital Region are working together.

“These agents in eastern and northern states are functioning in a joint racket under the same syndicate based in New Delhi,” said Rakesh Sengar, director of victim assistance in BBA.

Exploiting poverty

Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi’s Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA) has identified Rangia railway station in Assam as a transit point for trafficked children from eastern states. Around 58 girls, 18 of them from Lohardaga, were rescued from Doboka in Assam in September last year.

Girls from Gumla, Lohardaga, Khunti and Simdega are also taken to Chattisgarh or Orissa and handed over to agents who send them to other destinations.

The BBA also found that agents in Punjab, Haryana and the National Capital Region are working together.

“These agents in eastern and northern states are functioning in a joint racket under the same syndicate based in New Delhi,” said Rakesh Sengar, director of victim assistance in BBA.

Exploiting poverty

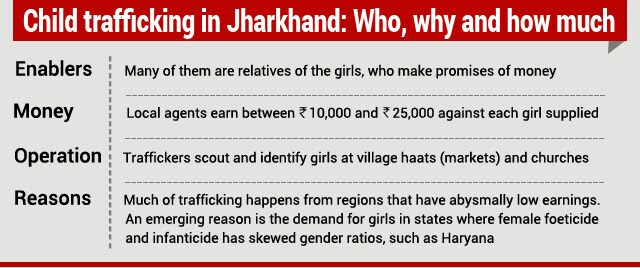

The rings have penetrated the remotest of villages in eastern India that are worst hit by poverty and hunger.

Rights activists claimed there are several villages without any teenagers, especially girls. Either they have migrated for jobs or have been trafficked. (Parwaz Khan/HT Photo)

“Blame poverty and the state’s neglect of the tribal population,” said Neel Justin Beck, a zila parishad member who has campaigned against trafficking for the past two decades in Simdega.

In the countryside of Gumla, Simdega and Khunti districts, animals are pricier than children, Beck said. “People are so poor that they worry for their cattle more than their missing children.”

Such is the apathy that thousands of girls from the three districts have gone missing over the past three decades but their families and the administration have been unable to locate them. There were even reports, Beck said, that girls from Simdega were trafficked as far as the Middle East.

Rights activists claimed there are several villages without any teenagers, especially girls. Either they have migrated for jobs or have been trafficked. In Palkot block of Gumla district, more than 500 girls have gone missing in the past five years, they said.

Done in by relatives

Many victims are sold to trafficking rings by their relatives. Like 12-year-old Somwari (name changed), a resident of Novatoli village in Lohardaga, who had no idea her uncle, who lived in her neighbourhood, would sell her for a few thousand rupees.

In the countryside of Gumla, Simdega and Khunti districts, animals are pricier than children, Beck said. “People are so poor that they worry for their cattle more than their missing children.”

Such is the apathy that thousands of girls from the three districts have gone missing over the past three decades but their families and the administration have been unable to locate them. There were even reports, Beck said, that girls from Simdega were trafficked as far as the Middle East.

Rights activists claimed there are several villages without any teenagers, especially girls. Either they have migrated for jobs or have been trafficked. In Palkot block of Gumla district, more than 500 girls have gone missing in the past five years, they said.

Done in by relatives

Many victims are sold to trafficking rings by their relatives. Like 12-year-old Somwari (name changed), a resident of Novatoli village in Lohardaga, who had no idea her uncle, who lived in her neighbourhood, would sell her for a few thousand rupees.

He took her to Chhattisgarh in an auto-rickshaw on the pretext of taking her to a fair, and sold her to a placement agent, who took her to Delhi by train.

Mukta Kumari, alias Lola, now 20, was sold to an agent in Goa by her cousin. She was rescued after two years.

“For unemployed men, women and even village heads, luring gullible girls and selling them to placement agencies has become a new income generation opportunity,” said Baijnath Kumar, a member of the NGO Divya Sewa Sansthan.

Pointing to his crumbling hut, 65-year-old Lode Khadia of Bangru village in Gumla justified the migration of girls to other states for jobs.

“We do not have BPL cards, old age pensions or jobs under MNREGA. During summers, we survive on wild berries. Wherever they go, I am sure at least they get good food to eat,” said the old man whose four daughters migrated years ago and never returned. He doesn’t worry for them.

His neighbour Bhondi Devi said many girls who went missing returned with children in their laps but could not reveal who had fathered them.

Despite the presence of tough laws, trafficking of children has continued unabated from Jharkhand. The BBA says it rescued almost 80,000 children across India, of whom 15% to 20% were from Jharkhand and Bihar.

“Police in Jharkhand, Bihar and Chhattisgarh will work together to bust the flourishing rackets and syndicates,” said inspector general (organised crime) Sampat Mina.

“Coordination between police departments of the concerned states is a must to bring an end to the illegal trade,” said Rishi Kant, founder-member of Delhi-based NGO Shakti

No comments:

Post a Comment